This year will not be marked by freight rates collapsing due to overcapacity and shippers weary from tariff costs reaping a windfall in ocean freight discounts. Despite the largest order book in history and volumes expected to slow globally, that is not the scenario coming into focus for the year ahead, even if widespread Red Sea transits resume.

Rather, according to several sources in recent weeks, a different picture is emerging: Rates will likely moderate, perhaps by a few hundred dollars per container, and as shippers realize that threats to service are not periodic but systemic, their focus on reliability will only intensify this year.

The year ahead, in other words, reflects long-term macro trends under way in containers: capacity tightening despite cyclicality due to infrastructure limitations and carrier actions to manage capacity, and shippers in response turning their focus away from rates and toward service to mitigate risk.

“For 2026 as we move into this bid season, it won't be all about the ocean rates,” Chantal McRoberts of Drewry Supply Chain Advisers told a recent Journal of Commerce webinar focused on Asia port congestion.

“We know that we're in a more subdued demand environment. We know that the order book is large. We know that carriers are looking to secure volume, but the key to that is, what service are you providing? Shippers are definitely starting to factor that into their bid strategies,” she said. “The number one question that comes up from BCOs [beneficial cargo owners] is, putting the rates aside, I need a reliable provider or partner to work with. I still have to answer to the CFO. I still have to justify the cost, but I now also have to ensure that I'm procuring my ocean freight to deliver my product.”

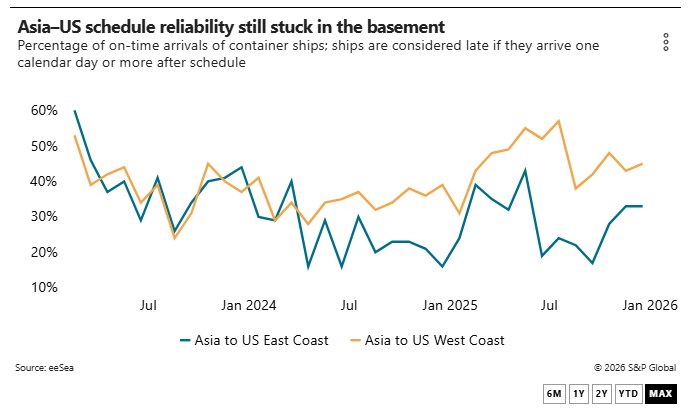

According to eeSea, ocean reliability from Asia to the US West Coast has ranged between 42% and 48% since September.

China ‘lacking port capacity’

Port congestion in China is a case in point about shippers' growing concerns about the integrity of supply chains.

Still the source of 36% of US imports in TEUs in 2025, (down from 40% in 2024), according to S&P Global Market Intelligence, the country is encountering chronic congestion at Shanghai and Ningbo, its two largest ports, where ships typically are waiting two to three days outside the port.

The fundamental reason, according to Asia sources over the past two years, was that while China ambitiously built port capacity ahead of demand in the years after entering the World Trade Organization in 2001, expansion has slowed at a time when its exports are experiencing a growth spurt.

“I know it's a shocker, and it feels unnatural to hear it, but China is lacking port capacity. It's as simple as that,” Nils Roche, founder of Solvens Advisory and recently deputy head of operations at Singapore-based carrier PIL, said on the Journal of Commerce webinar.

Limited port capacity in China is being called upon to handle surging volumes growing out of a macro-China economic strategy to diversify away from the US and overcome weakness in other sectors such as real estate.

China in November surpassed the $1 trillion trade surplus barrier for the first time. Its share of global exports grew from 33% to 37% between 2023 and 2025, Maersk told investors in November. Influenced by export growth, S&P Global Market Intelligence in November raised Mainland China's GDP growth forecast for 2025–27 by a quarter point, to 5.0%, 4.6% and 4.5%, respectively. “The upward adjustments primarily reflect a more positive assessment of export prospects,” S&P Global said.

The intractable nature of port capacity limitations is further reflected in growing ship sizes and more containers needed to be moved per port call at ports that have not kept pace.

“The ships that you have today, they are not the ships that we had 10 years ago. If you think about it, I used to operate Panamaxes, and they were the rock stars,” Roche said, noting his skepticism that technology-driven productivity improvements can meaningfully expand capacity. “Now you have 18,000, 24,000-TEU ships coming into the ports. A Panamax calling a port is a port call, a 24,000-TEU ship calling a port, it's a major event.”

The difficulty ports have in handling the volumes and ship sizes being thrown at them is confirmed by port performance data. The S&P Global Port Performance data is based on vessel turnaround time and normalized by workload, with underlying data provided by carriers — in other words, how many hours a ship is spending in port to achieve a certain move count. The data shows ports on a global basis are operating well below pre-pandemic levels of performance.

Due to port capacity limitations, Roche says the industry should temper its expectations for the impact of a return to the Red Sea, if that occurs this year (although there is no guarantee it will).

He said that if the Red Sea opens up, “we should not expect a massive influx of capacity, simply because the lack of capacity, or the bottleneck if you prefer, will be transferred from the ocean to the land.”

“I disagree with the narrative carried by analysts that shipping obeys 100% of the laws of supply and demand, and that more ships mean more supply ... it’s being half-blind to an entire ecosystem,” Roche said.